The Green Energy Graveyard: What Happens When a Wind Turbine Blade Dies?

The image is iconic: a sleek, white wind turbine spinning lazily against a blue sky, the ultimate symbol of a clean, sustainable future. We build them to save the planet from carbon emissions. But there is a dark irony hidden inside those massive, rotating blades. While they generate green energy for 20 years, their death creates a distinctly “un-green” problem.

We are currently facing a massive wave of “decommissioning.” The first generation of wind farms, built in the late 1990s and early 2000s, is reaching the end of its operational life. This leaves us with thousands of blades—some longer than a Boeing 747 wing—that need to go somewhere.

The problem is that these blades were designed to be indestructible. And because they were built to never fail, they are almost impossible to kill.

The Engineering Paradox

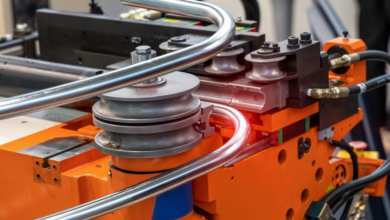

To withstand hurricane-force winds, constant UV exposure, and millions of rotations without snapping, turbine blades are marvels of composite engineering. They are typically constructed from a mix of balsa wood, fiberglass, and carbon fiber, all bound together by a thermoset resin (usually epoxy).

The keyword here is “thermoset.”

Unlike a plastic water bottle (a thermoplastic), which can be melted down and reformed into a new bottle, a thermoset composite is like a baked cake. Once the chemical reaction occurs during the curing process, the molecular bonds cross-link permanently. You cannot “un-bake” the cake. You cannot melt the resin down to recover the fibers.

Because of this chemical reality, the vast majority of retired wind turbine blades currently meet a crude and depressing fate: they are sawed into three pieces using diamond-tipped industrial cutters and buried in a landfill. In places like Casper, Wyoming, the “Blade Graveyard” has become a viral image—rows of massive fiberglass skeletons buried in the dirt, never to decompose.

The Quest for the Circular Blade

This disposal method is a PR nightmare for the renewable energy sector and a waste of valuable material. A wind blade contains tons of high-grade fiber. Burying it is essentially burying money.

This crisis has triggered a frantic innovation race within the material science sector. The goal is to solve the “separation anxiety”—how to separate the valuable fiber from the stubborn glue.

Three primary methods are currently fighting for dominance:

- Mechanical Grinding: This is the brute-force method. The blade is shredded into pellets. However, this destroys the length of the fibers, ruining their structural strength. The resulting material is basically “composite sawdust,” used only as cheap filler for asphalt or concrete. It’s a solution, but it’s a low-value one.

- Pyrolysis (Thermal Decomposition): This involves baking the chopped-up blade in an oxygen-free oven at intense heat (around 500°C). The resin burns off or turns into gas (which can be used to power the oven), leaving the clean fibers behind. While effective, it is energy-intensive and often degrades the strength of the recovered fiber, making it unsuitable for new aerospace or wind applications.

- Chemical Solvolysis: This is the “Holy Grail.” It involves using supercritical fluids or acids to chemically dissolve the resin at lower temperatures, washing the fibers clean without damaging them. If perfected at scale, this allows the carbon fiber to be reclaimed and reused in high-performance applications, closing the loop.

See also: How Smart Home Technology Is Redefining Interior Design

The Shift in Design

However, the real solution isn’t just better recycling; it’s better manufacturing. The industry is realizing that they cannot keep building “forever waste.”

This has led to the development of “reversible” resin systems. New startup technologies are introducing resins that behave like high-strength epoxies during their life but possess a chemical “kill switch.” When the blade retires, it can be dipped in a specific acidic solution that unlocks the molecular bonds, allowing the resin to dissolve and the pristine fiber to be recovered easily.

Major wind energy developers are now pledging “Zero Waste” goals, signaling that they will stop buying blades that cannot be recycled. This puts immense pressure on the supply chain.

A New Industrial Era

We are witnessing the end of the “linear economy” in composites (make, use, bury) and the painful birth of the “circular economy.”

The future of advanced materials is no longer just about stiffness-to-weight ratios; it is about end-of-life viability. The companies that will dominate the next decade won’t just be the ones who can build the strongest wing; they will be the ones who can un-build it.

Consequently, the most innovative carbon fiber manufacturing companies are no longer just selling strength; they are selling the promise of reversibility. They are acknowledging that for a material to be truly futuristic, it must be able to return to the beginning of the cycle, ensuring that the machines we build to save the environment don’t end up clogging it.